Highwarden Just (d)

Contact

Family

Personal

Highwarden Just (d)

Professional

Employment Information

Former

- Holsey InstituteEnd:08/1984

- TeacherHoward UniversityEnd:01/1969

Industry Information

Former

- Education/Academia: Higher Education

Highwarden Just (d)

Amherst

Reunion Class

- 1940

Other Academic

Secondary Schools

- Dunbar High School

Highwarden Just (d)

Amherst

Post-Graduate

Biography

Highwarden was born in 1918. He was the son of Ernest Just and Ethel Highwarden. He passed away in 1984.

Uncover new discoveries and connections today by sharing about people & moments from yesterday.- Discover how AncientFaces works.

- Highwarden Just was born to Ernest Everett Just (1883 - 1941) and Ethel William Highwarden (1885 - 1959). His father was born in South Carolina and his mother was born in Ohio. He had two sisters: Margaret and Mirabel Just. Highwarden married and they had one daughter.

- 12/201918December 20, 1918BirthdateWashington DC, District Of Columbia United StatesBirthplaceADVERTISEMENT BYView 2 birth records

- Highwarden was Black. His father was born in South Carolina and his mother was born in Ohio.

- In 1940, Highwarden worked for Howard University.

- On his World War II draft card, Highwarden was described as being 5 feet 9 inches tall and as weighing 130 pounds. He had brown eyes, brown hair, and a "light brown" complexion. He was married and had one daughter.

Biography

Biologist Dr. Ernest Everett Just was awarded the first Spingarn Award by the NAACP for his pioneering work in the field of biology. A meticulous "genius" in the design and process of experiments, a prolific writer, and an ardent researcher, he was the first American scientist ever invited to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, then a world-renowned research facility in Berlin. He worked in marine biology, embryology, cytology, and parthenogenesis, advocating the study of whole cells in their natural environments rather than breaking them apart in a laboratory setting.[1]

He was born in South Carolina on 14 August 1883 to Charles Frazier Just Jr. and Mary Anne Matthews. His father and grandfather, Charles Sr., were builders. They both died in 1887 when Ernest was just four years old.[2] To support the family of six, Ernest's mother taught school, and during the summer months she worked in the phosphate mines on James Island, South Carolina.[1][2] Mary later remarried, and also came to have a town named in her honor, Maryville, South Carolina.[1][2] Ernest was listed on the 1900 census records of Sullivan Island under his stepfather's last name (Williams), in Maryville/St. Andrew's Township, Charleston, South Carolina.[3]

By age sixteen, Ernest had earned a teaching degree from the Colored Normal Industrial Agricultural and Mechanical College of South Carolina (now South Carolina State University). But Mary and Ernest knew he was capable of more, and knowing the schools in the north were better, she sent him to Kimball Academy in Meriden, New Hampshire.[1][2] In his second year there the school burned down and he returned to South Carolina, only to find his mother had been buried an hour before his arrival.[1] Brokenhearted, he never returned to South Carolina again.[2] He redoubled his efforts at school and finished the four-year program in three years-- and at the top of his class.[1]

He enrolled at Dartmouth College, and there he became interested in biology. The only Black man in his graduating class, he graduated magna cum laude in 1907, winning numerous prizes and honors in sociology, history, botany, and zoology.[1] Although he was the only magna cum laude recipient in his class and was named its Valedictorian, due to "the cultural biases of the time" he was denied the opportunity to deliver the traditional Valedictorian address.[4]

In spite of his achievements, upon graduation his best academic offer was a job teaching English at Howard University; two years later Howard offered him a position teaching biology as well. He established and became the head of Howard's Department of Zoology,[1] and was able to focus entirely on science.[5] Although initially discouraged by the lack of opportunities for Black scientists to conduct research, through a Dartmouth contact he eventually came to the notice of Frank Lillie, Director of the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.[5] He was invited to to intern with Lillie and was quickly promoted to lab assistant in 1909.[1][2] He was the first African American to study and work at the Marine Biological Laboratory.[6]

He married Ethel Highwarden, who taught German at Howard University,[1] in 1912 in Washington, D.C.[7] They had three children:

- Margaret Just (1913)

- Highwarden Just (1918)

- Maribel Just (1922)

Ernest took a leave of absence from Howard and earned his Ph.D. summa cum laude in 1916 from the University of Chicago;[6] he was the first African-American to earn a doctorate there.[1][2] He continued to work almost every summer for the rest of his life at the MBL, and his work there brought him international notice and respect. Unable to find research opportunities in his own country, he went abroad to research in Italy, France, and Germany; he published over seventy academic papers.[6] His scientific ideas were described as innovative and radical.[2]

His first marriage ended in 1939, and that same year Ernest married Hedwig Schnetzler in Germany.

At the time of his second marriage, Ernest was working at the marine biology Station Biologique in Roscoff, Britany, France. When the Germans invaded in 1940, he was researching the paper that would become Unsolved Problems of General Biology, and did not evacuate when the French government requested foreigners to do so. He was interned in a prisoner-of-war camp. His wife, a German citizen, contacted the U.S. State Department for help returning him to the United States.[1] They traveled to the United States aboard the S. S. Excambion from Lisbon, Portugal on 4 September 1940.[8]

Ernest had been ill before his imprisonment and upon his return home received a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. He died in October 1941 at 58 years old, and was buried at Lincoln Memorial Cemetery in Suitland, Maryland.[1]

Legacy

- 1983 - Biography by Kenneth R. Manning, Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just; received the 1983 Pfizer Award and was a finalist for the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography.

- 1994 - The first award and and lecture dedicated to Dr. Just by the American Society for Cell Biology.

- 1996 - The U.S. Postal Service issued a 32-cent commemorative stamp honoring Dr. Just.

- 2000 - The Medical University of South Carolina began hosting the annual Ernest E. Just Symposium to encourage students of color to pursue careers in the biomedical sciences and health professions.

- 2002 - Molefi Kete Asante included him in his book, 100 Greatest African Americans.

- 2008 - A National Science Foundation-funded symposium held at Howard University honored his scientific work.

- 2009 - Molecular Reproduction and Development dedicated a special issue containing papers contributed by many of the speakers at the 2008 symposium.

- 2013 - International symposium honoring Dr. Just held at the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples, Italy.

- 2018 - A children's book about Dr. Just, The Vast Wonder of the World: Biologist Ernest Everett Just, written by Mélina Mangal and illustrated by Luisa Uribe, was published by Millbrook Press.

Sources

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Wikipedia contributors, "Ernest Everett Just," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 17 Jan. 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 "Dr. Ernest Everett Just," Capital Region Ques Member Portal, online article, accessed 20 February 2021. The website has moved to http://www.capitalregionques.org and is now a members-only site.

- ↑ "United States Census, 1900", database with images, FamilySearch (ark:/61903/1:1:M3RF-MS5 : Sat Apr 22 00:09:16 UTC 2023), Entry for Ernest Williams, 1900.

- ↑ "E.E. Just: Scientific Pioneer, Member of the Class of 1907," The Call to Lead: A campaign for Dartmouth, February 12, 2021, Dartmouth University.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Karen Wellner, "Ernest Everett Just" (1883-1941), Embryo Project Encyclopedia, Arizona State University (16 June 2010).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Mélina Mangal, "Ernest Everett Just (1883-1941) MBL Affiliation from 1909 to 1941 as Investigator and Corporation Member," the University of Chicago Marine Biological Laboratory.

- ↑ "District of Columbia Marriages, 1811-1950," database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QK9B-Y12Z : 15 January 2021), Ernest E Just and Ethel Highwarden, 26 Jun 1912; citing p. 57496, Records Office, Washington D.C.; FHL microfilm 2,051,877.

- ↑ "New York, New York Passenger and Crew Lists, 1909, 1925-1957," database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:24LS-KRS : 11 December 2020), Ernest E Just, 1940; citing Immigration, New York, New York, United States, NARA microfilm publication T715 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

See also:

- Wikidata: Item Q724591

- His parents and sister in "United States Census, 1880," database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M6SM-7BB : 13 November 2020), Just in household of Charles Just, Charleston, Charleston, South Carolina, United States; citing enumeration district ED 59, sheet 140B, NARA microfilm publication T9 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), FHL microfilm 1,255,222.

- "United States Census, 1910," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MKL2-KNH : accessed 12 February 2021), Earnest E Just in household of Richard E Schuh, Precinct 10, Washington, District of Columbia, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 202, sheet 9B, family 180, NARA microfilm publication T624 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1982), roll 155; FHL microfilm 1,374,168.

- "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-8BTZ-F8P?cc=1968530&wc=9FHK-W3D%3A928310901%2C928373801 : 24 August 2019), District of Columbia > District of Columbia no 8; Fagan, Edward-Stewart, Hershall H. > image 2177 of 5726; citing NARA microfilm publication M1509 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

- "United States Census, 1920," database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MNLB-Z35 : 1 February 2021), Ernest Just, 1920. Washington, District of Columbia, United States

- "New York, New York Passenger and Crew Lists, 1909, 1925-1957," database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:24F1-JR6 : 11 December 2020), Ernest E Just, 1930; citing Immigration, New York, New York, United States, NARA microfilm publication T715 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

- "United States Census, 1940," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K73W-M2M : 24 May 2020), Ernest Just, Tract 34, District of Columbia, Police Precinct 13, District of Columbia, District of Columbia, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 1-515, sheet 11B, line 68, family 174, Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940, NARA digital publication T627. Records of the Bureau of the Census, 1790 - 2007, RG 29. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2012, roll 571.

- Selassie, W. Gabriel. “Ernest Everett Just (1883-1941),” ‘’Black Past’’, online article, 30 January 2007 (https://www.blackpast.org : accessed 20 February 2021); citing Kenneth Manning’s ‘’Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983) and Kwame Anthony Appiah & Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African & African American Experience (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005) BlackPast.org.

- Distinguished African American Scientists of the 20th Century (Oryx Press, 1996) pp. 201-204.

Biography

Ethel was the daughter of W. Highwarden and Ida Belle Johnson. She was born and raised in Ohio, and graduated from Ohio State University.[1]

Sources

- ↑ "COVER: MARGARET JUST BUTCHER BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE." Negro History Bulletin 20, no. 1 (1956): 15. Accessed February 22, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44215203.

- "Ohio, County Births, 1841-2003", database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VRMD-P84 : 1 January 2021), Ethel Highwarden, 1885.

- "District of Columbia Marriages, 1811-1950," database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QK9B-Y128 : 15 January 2021), Ernest E Just and Ethel Highwarden, 26 Jun 1912; citing p. 57496, Records Office, Washington D.C.; FHL microfilm 2,051,877.

See also:

- "United States Census, 1900," database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MMZT-9KF : accessed 21 February 2021), Ethel W Highwarden in household of William H Beason, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 74, sheet 3B, family 63, NARA microfilm publication T623 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1972.); FHL microfilm 1,241,268.

- "United States Census, 1910," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MKLV-Q1Q : accessed 21 February 2021), Ethel W Highwarden in household of Hugh H Denney, Precinct 8, Washington, District of Columbia, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 163, sheet 12A, family 214, NARA microfilm publication T624 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1982), roll 153; FHL microfilm 1,374,166.

- "United States Census, 1920", database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MNLB-Z3R : 1 February 2021), Ethel Just in entry for Ernest Just, 1920.

- "United States Census, 1940," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K73W-SP8 : 24 May 2020), Ethel Just in household of Ernest Just, Tract 34, District of Columbia, Police Precinct 13, District of Columbia, District of Columbia, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 1-515, sheet 11B, line 69, family 174, Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940, NARA digital publication T627. Records of the Bureau of the Census, 1790 - 2007, RG 29. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2012, roll 571.

The Black Women Code Breakers of Arlington Hall Station

Their top-secret unit played a critical role during World War II.

Sheryl Everett Wormley remembers her grandmother Ethel Just as an accomplished scholar and collegiate educator who broke barriers for Black women during the Jim Crow era. With a bachelor’s degree from Ohio State and a master’s from Boston University, Just became dean of women at South Carolina State University around 1950.

Those probably weren’t her only career achievements, although the others are harder to trace. During World War II, a unit of African American women secretly worked as code breakers in Arlington as part of America’s massive intelligence operation, which employed roughly 10,000 women code breakers in total. By deciphering encrypted communications, the women helped the Allied forces target Axis leaders and enemy ships—and even coordinate the D-Day invasion.

Their command center was Arlington Hall Station, a former women’s junior college that became a key wartime cryptography center. (Today it houses the George P. Shultz National Foreign Affairs Training Center at George Mason Drive and Route 50.) The station was unusual for the time in that up to 15% of its workforce was Black—an effort at equity that Eleanor Roosevelt may have dictated herself, according to author Liza Mundy’s book, Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II.

But between the top-secret nature of the work and the racial segregation of the period, even people working at Arlington Hall were unaware that Just’s special unit existed. Whereas stories of their white counterparts have come to light as records have been declassified, the identities of most of Arlington’s Black code breakers remain unknown.

In researching her book, Mundy scoured National Security Agency records, among many other sources, and uncovered only two names of Arlington’s Black women code breakers: Annie Briggs, who headed up the production unit, which worked to identify and decipher codes; and Ethel Just, who led a team of translators.

William Coffee, a Black man, supervised the women and recruited many of them, later winning an award for his wartime leadership.

Genealogical and newspaper archives suggest that the Ethel Just of Arlington Hall was likely Ethel Highwarden Just, a Howard University language professor who married pioneering Black biologist Ernest Everett Just. The couple lived in Washington, D.C., and had three children before they divorced around 1939.

Although definitive proof of Just’s role in the code breaking unit is elusive, the October 1956 edition of The Negro History Bulletin (a periodical launched in 1937 by African American historian Carter G. Woodson) states that Ethel Just worked as a “translator in the War Department.”

“William Coffee may have known people who attended or taught at Howard,” Mundy says. “It wouldn’t surprise me at all if the country’s historically Black colleges and universities contributed many members of the code breaking unit.”

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Just in 1925 | |

| Born | 14 August 1883 |

| Died | 27 October 1941 (aged 58) Washington D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Lincoln Memorial Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Dartmouth College University of Chicago |

| Known for | marine biology cytology parthenogenesis |

| Awards | Spingarn Medal (1915) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | biology, zoology, botany, history, and sociology |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Frank R. Lillie |

Ernest Everett Just (August 14, 1883 – October 27, 1941) was a pioneering biologist, academic and science writer. Just's primary legacy is his recognition of the fundamental role of the cell surface in the development of organisms. In his work within marine biology, cytology and parthenogenesis, he advocated the study of whole cells under normal conditions, rather than simply breaking them apart in a laboratory setting.

Early life and education

[edit]Born to Charles Just Jr. and Mary (Matthews) Just on August 14, 1883, Just was one of five children. His father and grandfather, Charles Sr., were builders. When Just was four years old, both his father and grandfather died (the former of alcoholism).[1] Just's mother became the sole supporter of Just, his younger brother, and his younger sister. Mary Matthews Just taught at an African-American school in Charleston to support her family. During the summer, she worked in the phosphate mines on James Island. Noticing that there was much vacant land near the island, Mary persuaded several black families to move there to farm. The town they founded, now incorporated in the West Ashley area of Charleston, was eventually named Maryville in her honor.[2]

When Just was young, he became severely sick for six weeks with typhoid. Once the fever passed, he had a hard time recuperating, and his memory had been greatly affected. He had previously learned to read and write, but now had to relearn. His mother had been very sympathetic in teaching him, but after a while she gave up.[3]

Hoping Just would become a teacher, at the age of 13 his mother sent him to the "Colored Normal Industrial Agricultural and Mechanical College of South Carolina", the only 1890 land grant school for the education of Negroes in South Carolina, later known as South Carolina State University in Orangeburg, South Carolina. Believing that schools for blacks in the south were inferior, Just and his mother thought it better for him to go north. At the age of 16, Just enrolled at the Meriden, New Hampshire, college-preparatory high school Kimball Union Academy. During Just's second year at Kimball, he returned home for a visit only to learn that his mother had been buried an hour before he arrived.[3] Despite this hardship, Just completed the four-year program in only three years and graduated in 1903 with the highest grades in his class.[4]

Just went on to graduate magna cum laude from Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, class of 1907.[5] There, Just developed an interest in biology after learning about fertilization and egg development.[6] Just won special honors in zoology, and distinguished himself in botany, history, and sociology as well. He was also honored as a Rufus Choate scholar for two years and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.[4]

Just was a candidate to deliver a commencement speech, but was not chosen because the faculty "decided it would be a faux pas to allow the only black in the graduating class to address the crowd of parents, alumni, and benefactors. It would have made too glaring the fact, that Just had won just about every prize imaginable,"[3] including honors in botany, sociology, and history.[6] While teaching at Howard University, Just earned a PhD in 1916 from the University of Chicago, becoming the first African American to do so.[7]

Founding of Omega Psi Phi

[edit]On November 17, 1911, Ernest Just and three Howard University students (Edgar Amos Love, Oscar James Cooper, and Frank Coleman), established the Omega Psi Phi fraternity on the campus of Howard. Love, Cooper, and Coleman had approached Just about establishing the first black fraternity on campus. Howard's faculty and administration initially opposed the idea of establishing the fraternity, fearing that it could pose a political threat to Howard's white administration. However, Just worked to mediate the controversy and, despite the initial doubts, Omega Psi Phi, Alpha Chapter, was chartered on Howard's campus on December 15, 1911. Omega Psi Phi was incorporated under the laws of the District of Columbia on October 28, 1914.[1]

Career

[edit]When he graduated from Dartmouth, Just faced the same problems all black college graduates of his time did: no matter how brilliant they were or how high their grades were, it was almost impossible for black people to become faculty members at white colleges or universities. Just took what seemed to be the best choice available to him and accepted a teaching position at historically black Howard University in Washington, D.C. In 1907, Just first began teaching rhetoric and English, fields somewhat removed from his specialty. By 1909, however, he was teaching not only English but also Biology.[8] In 1910, he was put in charge of a newly formed biology department by Howard's president, Wilbur P. Thirkield and, in 1912, he became head of the new Department of Zoology, a position he held until his death in 1941.

Not long after beginning his appointment at Howard, Just was introduced to Frank R. Lillie, the head of the Department of Zoology at the University of Chicago. Lillie, who was also director of the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) at Woods Hole, Massachusetts, invited Just to spend the summer of 1909 as his research assistant at the MBL. During this time and later, Just's experiments focused mainly on the eggs of marine invertebrates. He investigated the fertilization reaction and the breeding habits of species such as Platynereis megalops, Nereis limbata, and Arbacia punctulata. For the next 20 or so years, Just spent every summer but one at the MBL.

While at the MBL, Just learned to handle marine invertebrate eggs and embryos with skill and understanding, and soon his expertise was in great demand by both junior and senior researchers alike.[9] In 1915, Just took a leave of absence from Howard to enroll in an advanced academic program at the University of Chicago. That same year, Just, who was gaining a national reputation as an outstanding young scientist, was the first recipient of the NAACP's Spingarn Medal, which he received on February 12, 1915. The medal recognized his scientific achievements and his "foremost service to his race."[3]

He began his graduate training with coursework at the MBL: in 1909 and 1910 he took courses in invertebrate zoology and embryology, respectively, there. His coursework continued in-residence at the University of Chicago. His duties at Howard delayed the completion of his coursework and his receipt of the Ph.D. degree.[9] However, in June 1916, Just received his degree in zoology, with a thesis on the mechanics of fertilization. Just thereby became one of only a handful of blacks who had gained the doctoral degree from a major university. By the time he received his doctorate from Chicago, he had already published several research articles, both as a single author and a co-author with Lillie.[8] During his tenure at Woods Hole, Just rose from student apprentice to internationally respected scientist. A careful and meticulous experimentalist, he was regarded as "a genius in the design of experiments."[10] He had explored other areas including: experimental parthenogenesis, cell division, cell hydration and dehydration, UV carcinogenic radiation on cells, and physiology of development.[6]

Just, however, became frustrated because he could not obtain an appointment at a major American university. He wanted a position that would provide a steady income and allow him to spend more time with his research. Just's scientific career involved a constant struggle for an opportunity for research, "the breath of his life". He was condemned by racism to remain attached to Howard, an institution that could not give full opportunity to ambitions such as the ones Just had due to budgetary constraints of the era.[9] Nevertheless, Just was able to make significant contributions to his field during this period, including co-authoring the textbook General Cytology, first published in June 1924, with other pioneers in cell biology, including Clarence Erwin McClung, Margaret Reed Lewis, Thomas Hunt Morgan and Edmund Beecher Wilson.[11] In 1929, Just traveled to Naples, Italy, where he conducted experiments at the prestigious zoological station "Anton Dohrn".

Then, in 1930, he became the first American to be invited to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin-Dahlem, Germany, where several Nobel Prize winners carried out research. Altogether from his first trip in 1929 to his last in 1938, Just made ten or more visits to Europe to pursue research. Scientists treated him like a celebrity and encouraged him to extend his theory on the ectoplasm to other species.[9] Just enjoyed working in Europe because he did not face as much discrimination there in comparison to the U.S. and when he did encounter racism, it invariably came from Americans.[3] Beginning in 1933, when the Nazis began to take the control Germany, Just ceased his work there. He moved his European-based studies to Paris and to the marine laboratory at the French fishing village of Roscoff, located on the English Channel.

Just authored two books, Basic Methods for Experiments on Eggs of Marine Animals (1939) and The Biology of the Cell Surface (1939), and he also published at least seventy papers in the areas of cytology, fertilization and early embryonic development.[12] He discovered what is known as the fast block to polyspermy; he further elucidated the slow block, which had been discovered by Fol in the 1870s; and he showed that the adhesive properties of the cells of the early embryo are surface phenomena exquisitely dependent on developmental stage.[13] He believed that the conditions used for experiments in the laboratory should closely match those in nature; in this sense, he can be considered to have been an early ecological developmental biologist.[14] His work on experimental parthenogenesis informed Johannes Holtfreter's concept of "autoinduction"[15] which, in turn, has broadly influenced modern evolutionary and developmental biology.[16] His investigation of the movement of water into and out of living egg cells (all the while maintaining their full developmental potential) gave insights into internal cellular structure that is now being more fully elucidated using powerful biophysical tools and computational methods.[17][18][19][20] These experiments anticipated the non-invasive imaging of live cells that is being developed today. Although Just's experimental work showed an important role for the cell surface and the layer below it, the "ectoplasm," in development, it was largely and unfortunately ignored.[3][21] This was true even with respect to scientists who emphasized the cell surface in their work. It was especially true of the Americans; with the Europeans, he fared somewhat better.[9]

Personal life

[edit]On June 12, 1912, he married Ethel Highwarden, who taught German at Howard University. They had three children: Margaret, Highwarden, and Maribel. The two divorced in 1939.[6] That same year, Just married Hedwig Schnetzler, who was a philosophy student he met in Berlin.[6]

In 1940, Just was imprisoned by German Nazis, but was easily released thanks to the help of his wife's father.[6]

Death

[edit]At the outbreak of World War II, Just was working at the Station Biologique in Roscoff, researching the paper that would become Unsolved Problems of General Biology. Although the French government requested foreigners to evacuate the country, Just remained to complete his work. In 1940, Germany invaded France, and Just was briefly imprisoned in a prisoner-of-war camp. With the help of the family of his second wife, a German citizen, he was rescued by the U.S. State Department and he returned to his home country in September 1940. However, Just had been very ill for months prior to his encampment and his condition deteriorated in prison and on the journey back to the U.S. In the fall of 1941, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and died shortly thereafter.[22]

Legacy

[edit]Just was the subject of the 1983 biography Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just by Kenneth R. Manning. The book received the 1983 Pfizer Award and was a finalist for the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography.[23][24] In 1996, the U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp honoring Just.[25]

Beginning in 2000, the Medical University of South Carolina has hosted the annual Ernest E. Just Symposium to encourage non-white students to pursue careers in biomedical sciences and health professions.[26] In 2008, a National Science Foundation-funded symposium honoring Just and his scientific work was held on the campus of Howard University, where he was a faculty member from 1907 until his death in 1941. Many of the speakers at the symposium contributed papers to a special issue of the journal Molecular Reproduction and Development dedicated to Just that was published in 2009.

Since 1994, the American Society for Cell Biology has given an award[27] and hosted a lecture in Just's name. At least two of the institutions with which Just was associated have established prizes or symposia in his name: The University of Chicago Archived 2018-09-07 at the Wayback Machine,[28] where Just received his PhD (in zoology, in 1916), and Dartmouth College, where he received his undergraduate degree. In 2013, an international symposium honoring Just was held at the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples, Italy, where Just had worked starting in 1929.[29][30][31][32]

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Just on his list of the 100 Greatest African Americans.[33] A children's book about Just, titled The Vast Wonder of the World: Biologist Ernest Everett Just, written by Mélina Mangal and illustrated by Luisa Uribe, was published by Millbrook Press in November 2018.

Just believed that "life as an event lies in a combination of chemical stuffs exhibiting physical properties; and it is in this combination, i.e., its behavior and activities, and in it alone that we can seek life.".[34] He also wrote: "[L]ife is the harmonious organization of events, the resultant of a communion of structures and reactions",[13] and "We [scientists] have often striven to prove life as wholly mechanistic, starting with the hypothesis that organisms are machines! Living substance is such because it possesses this organization--something more than the sum of its minutest parts"[35] He argued forcefully that the "ectoplasm," the outer region of the cytoplasm, and not the nucleus, constitutes the heart of the dynamic cell. He was convinced that the surface of the egg cell possesses an "independent irritability," which enables the egg (and all cells) to respond productively to diverse stimuli.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ a b The Capital Region Ques[usurped], accessed March 14, 2013.

- ^ Donna Jacobs, "A BIT ON MARYVILLE - The People, Trials, and Tribulations of one of Charleston's first black enclaves" Archived 2013-05-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Manning, Kenneth R. (1983). Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195034981.

- ^ a b Ernest Just Archived 2010-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, Black Inventor Museum. Accessed October 11, 2009.

- ^ Kelsey, Elizabeth. "Expansive Vision, Ahead of His Time: Dartmouth celebrates biologist E. E. Just, Class of 1907". Dartmouth Life. Dartmouth College. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ^ a b c d e f "Ernest Everett Just". Biography. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ^ "Future Intellectuals: Ernest Everett Just (PhD 1916)". University of Chicago. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Lee, Edward (March 2006). "Ernest Everett Just". Blacfax: 15–16.

- ^ a b c d e Lillie, Frank (1942). "Obituary". Science. 95 (2453): 10–11. doi:10.1126/science.95.2453.10. PMID 17752140.

- ^ Jeffery, William R. (1983), "Ernest Everett Just (1883-1941): a dedication. Biological Bulletin 165: 487.

- ^ Chambers, Robert; Conklin, Edwin G.; Cowdry, Edmund V.; Jacobs, Merkel H.; Just, Ernest E.; Lewis, Margaret R.; Lewis, Warren H.; Lillie, Frank R.; Lillie, Ralph S.; McClung, Clarence E.; Mathews, Albert P.; Morgan, Thomas H.; Wilson, Edmund B. (1925). Cowdry, Edmund V. (ed.). General Cytology: A Textbook of Cellular Structure and Function for Students of Biology and Medicine (Second ed.). Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226251257. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ "Ernest Everett Just". San Jose State University Virtual Museum. Archived from the original on 2009-06-04. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ a b Just, E. E. (1939), The Biology of the Cell Surface. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston's Son and Co., Inc.

- ^ Byrnes, W. Malcolm; William R. Eckberg (2006). "Ernest Everett Just (1883-1941)--an early ecological developmental biologist". Dev. Biol. 296 (1) (August 1, 2006), pp. 1–11.

- ^ Byrnes, W. Malcolm (2009) Ernest Everett Just, Johannes Holtfreter, and the origin of certain concepts in embryo morphogenesis. Molecular Reproduction and Development 76 (11): 912-921

- ^ Kirschner, M. W.; J. C. Gerhart (2005), The Plausibility of Life: Resolving Darwin's Dilemma. New Haven: Yale University Press

- ^ Just, E. E. (1939), "Water" In: The Biology of the Cell Surface. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston's Son and Co., Inc., pp. 124–146.

- ^ Charras, G. T.; T. J. Mitchison; L. Mahedevan (2009), "Animal cell hydraulics". J. Cell Sci. 122 (18): 3233–3241.

- ^ Needleman, D.; J. Brugues (2014), "Determining physical principles of subcellular organization". Dev. Cell 29: 135–138.

- ^ Byrnes, W. Malcolm; Stuart A. Newman (2014), "Ernest Everett Just: Egg and Embryo as Excitable Systems". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B (Molecular and Developmental Evolution) 322 (4): 191–201.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F. (1988), "Cellular politics: Ernest Everett Just, Richard B. Goldschmidt, and the attempt to reconcile embryology and genetics". In: Rainer R., D. Benson, J. Maienschein (eds), The American Development of Biology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 311–346.

- ^ Byrnes, W. Malcolm; Eckberg, William R. (2006). "Ernest Everett Just (1883–1941)—An early ecological developmental biologist". Developmental Biology. 296 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.445. PMID 16712833.

- ^ "Pulitzer for Fiction Won by Author of 'Ironweed'". The Spokesman-Review. April 16, 1984. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ Garland E. Allen (November 1998). "Life Sciences in the Twentieth Century". History of Science Society. Archived from the original on 2009-04-03. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ "Dr. Ernest E. Just Honored on New Black Heritage Stamp". Jet. February 26, 1996. p. 19.

- ^ Shantae D. James (March 20, 2003). "Summary Statement of the 3rd Annual Ernest E. Just Symposium". Medical University of South Carolina. Archived from the original on September 15, 2006. Retrieved 2009-10-23.

- ^ "E.E. Just Lecture Award" Archived 2014-09-03 at the Wayback Machine, ASCB.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-09-07. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ^ L. Santella & JT. Chun, "International Symposium - The dynamically active egg: The legacy of Ernest Everett Just" Archived 2014-09-04 at the Wayback Machine, Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn di Napoli, 13 maggio 2013.

- ^ Cristina Zagaria, "Just, biologo afroamericano che trovò la libertà a Napoli", La Repubblica, 11-05-2013.

- ^ W. Malcolm Byrnes, "Walking in the Footsteps of Ernest Everett Just at the Stazione Zoologica in Naples: Celebration of a Friendship", Howard University, May 15, 2013.

- ^ W. Malcolm Byrnes, Sulle orme di E.E. Just alla Stazione Zoologica di Napoli: celebrazione di un'amicizia Archived 2014-08-19 at the Wayback Machine, researchitaly, 01/07/2013.

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002), 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ^ Just, Ernest Everett (1988). The Biology of the Cell Surface (Facsimile ed.). New York: Garland Pub. ISBN 978-0824013806.

- ^ Just, E. E. (1933), "Cortical cytoplasm and evolution". Am. Nat. 67: 20–29.

- ^ Newman, Stuart A. (2009), "E. E. Just's 'independent irritability' revisited: The activated egg as excitable soft matter" Archived 2016-01-18 at the Wayback Machine. Molecular Reproduction and Development 76 (11): 966–974.

Further reading

[edit]- Manning, Kenneth R., Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

- Manning, Kenneth R. (2009), Reflections on E. E. Just, Black Apollo of Science, and the experiences of African American scientists. Molecular Reproduction and Development 76 (11): 897–902.

- Sapp, Jan (2009), "'Just in time': Gene theory and the biology of the cell surface". Molecular Reproduction and Development 76 (11): 903–911.

- Crow, James F. (2008), "Just and Unjust: E. E. Just (1883-1941)". Genetics 179: 1735–1740.

- Grantham, Shelby (1983), "The Greatest Problem in American Biology..." Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, Volume 76, No. 3 (November 1983): 24–31.

- Grunwald, Gerald B. (2013), "A Century of Cell Adhesion: From the Blastomere to the Clinic Part 1: Conceptual and Experimental Foundations and the Pre-Molecular Era". Cell Communication and Adhesion 20: 127–138.

- Gilbert, Scott F. (1988), "Cellular politics: Ernest Everett Just, Richard B. Goldschmidt, and the attempt to reconcile embryology and genetics". In: Rainger, R., D. Benson, J. Maienschein (eds), The American Development of Biology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 311–346.

- Esposito, Maurizio (2013), Romantic Biology, 1890–1945. London: Pickering and Chatto. See especially pp. 134–143.

- Gould, S. J. (1985), "Just in the middle: A solution to the mechanist-vitalist controversy". In: The Flamingo's Smile: Reflections in Natural History. New York: W. W. Norton and Co., pp. 377–391.

- Gould, S. J. (1987), "Thwarted genius". In: An Urchin in the Storm: Essays About Books and Ideas. New York: W. W. Norton and Co., pp. 169–179.

- Cohen, S. S. (1986). "Balancing science and history: a problem of scientific biography. "Black Apollo of science: the life of Ernest Everett Just." By Kenneth R. Manning. Essay review". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. Vol. 8, no. 1. pp. 121–8. PMID 3534923.

- Dummett, C O (1985). "Unexpected historical peregrinations". The Journal of the American College of Dentists. Vol. 52, no. 2. pp. 28–31. PMID 3897332.

- Wynes, C E (1984). "Ernest Everett Just: marine biologist, man extraordinaire". Southern Studies. Vol. 23, no. 1. pp. 60–70. PMID 11618159.

- Brown, Mitchell, "Faces of Science: African-Americans in the Sciences" Archived 2006-09-19 at the Wayback Machine, 1996.

- Kessler, James, J. S. Kidd, Renee Kidd, and Katherine A. Morin, Distinguished African-American Scientists of the 20th Century. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press, 1996.

- McKissack, Patrick and Frederick. African-American Scientists. Brookfield, Connecticut: The Millbrook Press, 1994.

- Yount, Lisa. Black Scientists. New York: Facts on File, 1991.

Natur hat weder Kern

Noch Schale

Alles ist sie mit einem Male2

THIS year marks the 125th anniversary of the birth of Ernest Everett Just. He was one of the greatest biologists of the early 20th century, but being Afro-American, he never had a position that permitted full development of his research talent. The latter part of his life was a time of great frustration, for both professional and social reasons. Despite insufficient time for research and poor financial support, he published more than 70 articles and two books.

I first heard of Just during my graduate student days. J. T. Patterson, my major professor at the University of Texas, had mentioned his work in a lecture. Later, in the fall of 1941, I joined the faculty at Dartmouth College and learned of Just's death, which was on October 27. He had been a student there and my elderly colleague, John Gerould, remembered him well. I have been interested in him ever since, but I knew very little until the 1980s when I read Kenneth Manning's magnificent biography (Manning 1983). That is the source of most of the material in this essay.

EARLY DAYS

Ernest Just was born on August 14, 1883, in Charleston, South Carolina. His grandfather had been a slave, who inherited the Just name from his master and very likely a haploid genome as well, for he was the light-skinned favorite. Ernest's father loved alcohol and women. In addition to his wife he kept a mistress although he did not earn enough to support even one household. He died when Ernest was 4 years old.

Ernest's mother was a remarkable woman. After her husband's death she sold their home in Charleston and moved to James Island, off the coast of South Carolina, where she did manual work at a phosphate factory. This was an unusual job for a woman, but it paid better than any women's work. She managed to earn enough to invest in real estate. In addition, she quickly became a community leader and later founded the first school on the island. And she had great ambitions for her gifted son.

At age 13 Ernest enrolled at South Carolina State College, also known as The Colored Normal, Industrial, Agricultural, and Mechanical College, where he completed the regular 4-year course in 3 years. But instead of the expected teaching career, he and his mother decided he should get more education. Seeing an ad in the Christian Endeavor World for a private secondary school, Kimball Union Academy in Meriden, New Hampshire, they decided that he should apply for entrance.

Without knowing whether he would be admitted, Ernest took a ship to New York, working on board to pay his passage. He then did various jobs in the city for a few weeks, earning enough for the trip to New Hampshire. Surprisingly, he was admitted and in fact received a scholarship reserved for “deserving” students. He also worked part time, usually in the kitchen.

Just was determined to be a classical scholar and took courses in Latin and Greek. He also excelled in oratory and journalism. Having acquired his mother's administrative and organizational talents, he edited the student newspaper, won an oratory contest, and was chosen to deliver a commencement address. Clearly, he was the outstanding student in his class.

Dartmouth College was only a dozen miles away, so naturally he moved to that campus for his college education. He entered in the fall of 1903 at age 20. He remained interested in classics and continued his studies of Latin and Greek. As he had done at Kimball, he got involved in numerous activities. Among other things he wrote poetry and short stories, something he continued for the rest of his life. Some of these were printed in Dartmouth College publications. More important for his future life, his interests gravitated toward biology. He was especially attracted to William Patten, a distinguished paleontologist who was an influential faculty member and had a strong effect on Dartmouth's curriculum. Patten later organized a course in evolution, required of all freshmen. This must have required both leadership and courage, especially at a time when the Scopes Trial had made evolution highly controversial. Just did research projects for Patten and was duly acknowledged in his text. Another Dartmouth influence was J. H. Gerould, who was astonished at Just's brilliance and scientific skill. Gerould later became known for his genetic studies of butterflies. With more logic than social awareness, he wondered why a person who very likely had more than 50% white ancestry should be classified as Negro.3 Gerould retained admiration and affection for his brilliant student throughout Just's career.

Again, Just was a top student. In both his junior and senior years he was a Rufus Choate Scholar, Dartmouth's highest honor, particularly unusual for a junior, and he won the Grimes award for scholastic improvement during his 4 years. He graduated in 1907, magna cum laude.

HOWARD, CHICAGO, AND WOODS HOLE

With such an outstanding record Just might have been expected to have a number of employment opportunities. Actually, there were only two—at two Negro colleges, Morehouse and Howard. He chose Howard and his initial appointment was in the English Department. He taught various humanities subjects and was quickly recognized for his teaching skills. He was popular with students and active on committees and in various organizations. For example, he organized a drama club and produced Goldsmith's “She Stoops to Conquer.” He continued his interest in oratory and wrote poetry, as he had done at Dartmouth. By 1912 his reputation had spread well beyond Howard and in 1915 he received the Spingarn Medal of the NAACP, on the recommendation of Jacques Loeb.

In 1909 he began teaching biology courses and again his interest shifted away from classics and toward science, as had happened at Dartmouth. Thinking of graduate work in zoology, he sought Patten's advice. He was told that medicine was a better direction for an Afro-American; nevertheless, Patten recommended him to Frank R. Lillie, head of the Zoology Department at the University of Chicago. Lillie accepted him as his assistant at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, Massachusetts. So, in the summer of 1909, at age 26, Just began what was to be a highly successful association with that biologist's Mecca.

In the next few summers he earned a reputation as an excellent scientist. He worked closely with Lillie in the lab and they developed enormous mutual respect. Just quickly became known as particularly knowledgeable in the ways of doing research at this ocean laboratory. He was hard working and regularly went to sea on collecting expeditions. He became an expert collector of the various sea invertebrates, knowledgeable about where to find them. He was also a skilled microscopist. And he began to publish. His first article reported that, in the developing egg of the sea worm, Nereis, the first cleavage plane is determined by the point of entry of the sperm (Just 1912). This article attracted considerable favorable attention, for example, from T. H. Morgan, and marks the beginning of his rapidly growing reputation as a scientist. (I learned about this in an embryology course.) In the next 3 years he published four more articles. Later, his advice came to be sought so much as to become a serious encroachment on his research time.

Just had several close friends at Woods Hole. He enjoyed the company of A. H. Sturtevant and the two regularly ate together. He also spent time with geneticists Donald and Rebecca Lancefield and with cytologists Franz Schrader and Sally Hughes (Schrader) (Figure 1). With Sally he could indulge his passion for discussing poetry, literature, and music. In particular they shared an interest in D. H. Lawrence, whose writings were at that time considered quite scandalous. There were other friends. Just was handsome, intelligent, and personable and had a wide variety of interests, all of which made him very popular.

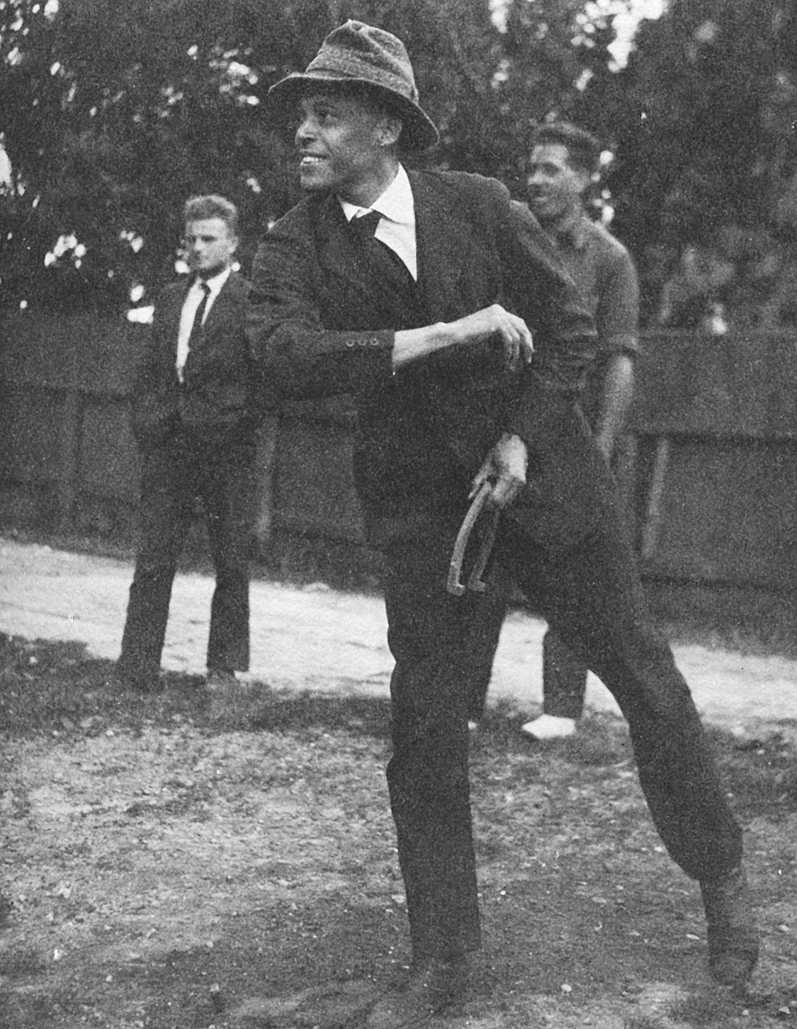

Figure 1.—

Ernest E. Just pitching horseshoes at Woods Hole, ca. 1912. The person to the left is Donald Lancefield, who began the study of the Drosophila pseudoobscura group, later exploited by Sturtevant and Dobzhansky. Reprinted with permission from Black Apollo of Science. The Life of Ernest Everett Just by Manning (1983).

The exciting science at Woods Hole and the happy association with Lillie led to his desire to do graduate work and Lillie was happy to accept him as a student. He applied for leave from Howard, but was turned down, so his graduate work had to be postponed. A year later he was successful and entered the University of Chicago in 1915. Several of the courses he had taken at Woods Hole were counted toward his graduate degree and he received his Ph.D. on June 6, 1916. He hoped that this might lead to a position with more research opportunities, but this was not to be. He stayed at Howard.

Just was a superb technician and extremely careful worker. He set rigorous standards for experimentation and was openly critical of experiments that did not meet his standards. Furthermore, he trusted his observations and did not hesitate to point out disagreements with others. The most notable of these was a difference with Jacques Loeb. Despite earlier happy associations with Loeb—he had recommended Just for the Spingard Award—Just thought that Loeb's work was flawed and said so (Just 1922). Loeb had argued that the development of the egg was initiated by two steps, a cytolysis, induced in the laboratory by butyric acid, followed by a quenching produced by hypertonic sea water. Just showed that, with careful attention to concentrations, sea water alone was sufficient. He thought that Loeb had missed this because of being inattentive to details. And Just had other criticisms. This led to quite a dustup and various embryologists took sides, some supporting Loeb and others supporting Just.4 Loeb and Just also differed philosophically. Loeb was a reductionist, searching for chemical and physical explanations, and his papers were often mathematical. Just was a holist and did not like math.

Earlier, Loeb had been a close friend of Just and admired him. Loeb's social views were liberal and he was a strong supporter of social causes. Negro colleges, Howard University in particular, were a special interest. Unfortunately for Just, Loeb's earlier friendship changed to enmity. One of the few opportunities that Just had for a position in a research environment occurred in 1923. Just was being considered for a position at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. Naturally Loeb's advice was sought and his reply left no uncertainty: “… the man is limited in intelligence, ignorant, incompetent, and conceited; in fact his research work is not only bad but a nuisance” (Manning 1983, p. 90). I do not know the extent to which Loeb's letter was influenced by personal disagreement, but I am sure that this ruined whatever chance Just had to get into a research environment. He had no choice but to remain at Howard with its time-consuming and intellectually draining teaching and committee responsibilities.5

Just continued to spend summers at Woods Hole. He obtained a grant from the National Research Council that let him spend half days at Howard on research. But often his other obligations spilled over into his research time, and he got less done than he had hoped. Nevertheless, he remained productive, especially in the summers at Woods Hole. By 1930 he had published some 50 articles, all substantial and showing his careful work and attention to details.

Meanwhile, things were not going well at Howard. The university was having administrative problems, and Just was caught up in them. His relationship with the university president deteriorated. His grant for research time ran out and his faculty duties seemed ever more oppressive. At the same time his relationships at the Marine Biology Lab were also souring. He found that too much of his time went to helping others. He feared that he would be regarded as only a follower of Frank Lillie. But above all, and surprising for this enlightened community, there were racist incidents. Just was used to having problems getting served in hotels and restaurants, but he was not prepared to find a problem at Woods Hole. He decided one summer to bring his wife and children with him. They encountered remarks that they regarded as offensive and immediately left. The brief encounters he had had in Europe, especially the biological station at the Bay of Naples, led him more and more to desire a move. He found European views of science to his liking and ready acceptance at restaurants and hotels made his life much more pleasant.

A man as intelligent and personable as Just would be expected to attract female companionship. The first of his affairs was with Margret Boveri, the daughter of none other than Theodor Boveri. Later, in 1931, Just met Hedwig Schnetzler, who became his companion and eventually his wife. An affair with a white woman, especially if the Afro-American man was married, would place his whole career at Howard in jeopardy. In Europe, although this was hardly encouraged, it was condoned. Hedwig had a large influence on him, both emotionally and intellectually. From his Dartmouth days, Just had an interest in philosophy. She shared this with him and I think she played a substantial part in his subsequent writing, which became more philosophical. His American colleagues were more interested in experimentation, whereas the Europeans were more accepting of theorizing. For all these reasons, his writing changed from strictly observational and experimental to more philosophical. This is reflected in his book, The Biology of the Cell Surface (Just 1939b).

SELF-IMPOSED EXILE IN EUROPE

After all his discouragements, Just decided to live in Europe. He had been in Naples, Berlin, and Paris. He and Hedwig planned to spend the rest of their lives together in Europe. Earlier he had heard live opera in Paris, something that he had never experienced in America. In Italy he heard high-quality chamber music for the first time, the Busch String Quartet being one example. He and Hedwig both enjoyed music, art, and reading. The only problem was how to find enough money to live in Europe.

His earlier trips had always involved financial problems. His Howard salary went mainly to his family. He had some success with foundations, but it was nip and tuck. Nevertheless, he made a number of trips to Europe, fitting these into times when he could get away from Howard.

He enjoyed the company of Reinhard Dohrn, director of the Statione Zoologica in Naples. He felt completely at home, scientifically and socially, with European scientists and, as already mentioned, he spent a great deal of time with Margret Boveri, who was secretary to Dohrn. It was a period of intense research activity, involving long hours in the laboratory, which he loved. Dohrn was also a lover of art and music. There were concerts in the main lobby of the Statione. He also encouraged Just in his philosophical interests.

Later Just spent time at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft in Dahlem. There he worked in the laboratory of Max Hartmann. It was an intellectually rich experience, for he associated regularly with Richard Goldschmidt, Otto Mangold, and Johannes Holtfreter. He had earlier become convinced that the outer layer of the cytoplasm, the ectoplasm, was of great importance and here he was able to extend his studies to Amoeba, taking advantage of its giant cell size.

After his decision to move to Europe, Just tried all sorts of ways to gain financial support. There was only limited opportunity for paid leave from Howard. He applied to one foundation after another, usually getting turned down. He even tried some well-known millionaires. His relations with the Rockefeller Foundation were typical. Although Warren Weaver, head of the Division of Natural Science, was sympathetic and respected Just's work, he thought, as others had, that the place where Just would do the greatest good for the African-American population was to stay at Howard. But this was precisely what Just did not want. He was desperate to get to Europe. He got a little help from the Carnegie Corporation, but it was hard going. For another facet of Weaver's career, see Crow (1995).

For a while Just had a desk at the Sorbonne, but no money. By 1939 he had got a European divorce and married Hedwig. They settled in a small biological station in Roscoff on the French coast overlooking the English Channel. The facilities were primitive, but there was an abundance of marine fauna. He and Hedwig were isolated, but this suited them. He continued experiments and, with Hedwig's help and encouragement, did more writing. He got no more money from Howard, but Hedwig's brother supplied some badly needed funds.

By 1940 the German armies had invaded Czechoslovakia and the siege of Paris had begun. Despite his love for German culture, Just hated Hitler. In contrast, America did not seem so bad, after all. His zoological colleagues, especially at Woods Hole, were worried about him and hoped for his return. Finally he and Hedwig decided that they must leave Europe. There were passport difficulties and Just was actually interned by the Nazis, but somehow his release was negotiated. Eventually they were able to book passage from Spain and sailed to New York. In the confusion of leaving, all of the Roscoff research records were lost. Furthermore, his health was deteriorating. He found himself getting weaker and he was in considerable pain. He tried to continue work at Howard, but it became increasingly difficult. Finally, after several false clues, the pain was diagnosed as pancreatic cancer. He died October 27, 1941. In 1996 he was commemorated by a postage stamp.

Lillie must have known Just better than any other American scientist. He wrote an obituary for Science (Lillie 1942). In his characteristic restrained way, he said

An element of tragedy ran through all Just's scientific career due to the limitations imposed by being a Negro in America, to which he could make no lasting psychological adjustment in spite of earnest efforts on his part. The numerous grants for research did not compensate for failure to receive an appointment in one of the large universities or research institutes. He felt this as a social stigma, and hence unjust to a scientist of his recognized standing. In Europe he was received with universal kindness, and made to feel at home in every way; he did not experience social discrimination on account of his race, and this contributed greatly to his happiness there. Hence, in part at least, his prolonged self-imposed exile on many occasions. That a man of his ability, scientific devotion, and of such strong personal loyalties as he gave and received, should have been warped in the land of his birth must remain a matter for regret. (Lillie 1942, p. 10–11)

SCIENTIFIC WORK

Just's first article (Just 1912) showed the characteristics for which he was soon to become greatly respected. He was thoroughly familiar with the organism, in this case the polychaete sea worm Nereis. He took great pains to find ways to keep the animals healthy, he tried many experimental conditions to find the best, and he reported in detail what he had done. He cleverly used fine particles of India ink to mark the sperm entrance point. In this article, in addition to supplying details about the fertilization process, he showed that the plane of the first cleavage division passes through the entry point of the sperm. This was reviewed in detail by Wilson (1925) in his classic textbook, where he said (p. 1104) “The most decisive evidence seems to be offered by Just's observations …”

His next article was done jointly with his teacher, Frank Lillie (Lillie and Just 1913). This tells you all you want to know about the life history and especially the breeding habits of Nereis. As was typical of the time, individual collections and experiments are described in full. This became the standard reference for others wanting to work on this species.

The next few years brought half a dozen more papers, giving more details of the fertilization process and the many experiments performed, not only on Nereis, but also on Platynereis, Echinarachnius, and Arbacia. Several of these followed up on Lillie's idea of “fertilizin,” a colloidal substance thought to form the bridge between egg and sperm. All these articles show the Just touch: careful observations, care in providing optimum living conditions, and meticulous attention to experimental details. By this time Just's reputation as the person who knew all the techniques for studying embryology of sea invertebrates was well established. Lillie's idea was controversial; Wilson (1925, p. 422) said “These conclusions should, perhaps, not be taken too literally; but they have the great merit of opening the way to exact experimental studies of the problems on the physiological side.” Just did not hesitate to interpret his data; sometimes the interpretations were dubious, but no one questioned his observations.

In a study of Echinarachnius, Just (1919) verified that an egg, as soon as a sperm enters, becomes impermeable to other sperms. His idea was that there are two events in the egg. The first is the liberation from the nucleus of a substance making the egg fertilizable; the second is the entrance of the sperm, which blocks any further sperm entry.

In addition to these experimental articles, Just also wrote a number of articles on the techniques of collecting material from the sea and detailed methods of performing experiments. This culminated in the publication of a book, based on his Woods Hole work (Just 1939a).

Just had long had an interest in philosophy. He also was willing to speculate. Neither of these was encouraged by his Woods Hole associates; they respected him for his careful experimental work. But in Europe, things were different; speculation and philosophy were encouraged. As a result, Just's later work moved in this direction.

For many years Just was concerned that the ectoplasm, the outer layer of the cytoplasm and membrane, was key to many cell activities. This was the part of the cell that is most directly in contact with external agents and other cells and therefore of special importance. From our present viewpoint, he clearly underestimated the importance of the chromosomes in development.

His later work covered several topics, embryology, evolution, and philosophy. Just was impressed by the genetics of the Morgan school. He said that the chromosome theory of heredity along with chromosome mapping was one of the great accomplishments of modern biology. But he held a view, not uncommon at the time, that although genetics had elegantly solved the problem of transmission from generation to generation, it fell short in explaining how the genetic information is translated into development and phenotype. For this he turned to the cytoplasm.

His article on mutation is interesting (Just 1932). He was much impressed by Muller's discovery of radiation-induced mutagenesis. He also noted that mutation was temperature dependent. From this he reasoned that the specificity of the mutation process lies in the chromosome, since the response to different treatments is characteristic of the particular gene, not the nature of the treatment. So far so good, but then he was off on his holistic cytoplasmic ideas again. “The gene theory is a conception too ultra-mechanistic to yield further profitable results” (Just 1932, p. 73). But he was candid and admitted that this was speculative. “To many readers this discussion doubtless will appear wholly illusory and fantastic. I own that it is speculative. But I offer it as a suggestion” (Just 1932, p. 74).

Just's views of the relationship between genetics and embryology were set forth at great length (46 pages) in an article entitled “A single theory for the physiology of development and genetics” (Just 1936). Here he rejected the view, put forth by some, that genetics and embryology are “nonoverlapping magisteria” (to employ Steve Gould's pomposity). He attempted a synthesis. This article reflects not only his wide erudition, but also his strong desire to emphasize the cytoplasm. His theory, briefly, is this. The egg starts out with a pluripotent cytoplasm. The process of chromosome synthesis that occurs in each cell division takes material from the cytoplasm to make copies of itself. This leaves the cytoplasm changed, and in particular changed so as to have a more restricted set of potencies. As development proceeds, somatic cells would have more restricted functions. To me, this represents a thoughtful approach to the problem, in many ways with a modern touch. But when he started to explain mutations, for example Drosophila eye colors, he was less convincing. But he was always careful to label his ideas as speculative.6

Just's view of a pluripotent cytoplasm that continually loses potencies because of material taken from it to copy chromosomes does not jibe with current ideas of gene regulation. Yet, at a time when there was essentially no understanding of developmental mechanisms and many treated embryology and genetics as entirely separate subjects, his attempt at a synthesis was at least a step in the direction of unification. And, typical of Just, it brought to bear observations from extensive and widely varied sources.

Just never abandoned his view of the primacy of the cytoplasm. Yet, in a later article (Just 1940), he speculated that genes are nucleic acid. Toward the end of his life he realized that the chemical study of nucleoproteins would be increasingly important. In outlining his plans for future research, he said he hoped to do “… a more exact study of nucleo-protein synthesis to embrace as many different types of eggs as possible” (Cohen 1985, p. 135). Alas, he did not live long enough to do this.

Just summarized his life work in his magnum opus, The Biology of the Cell Surface. It is a combination of beautiful and beautifully described experiments interspersed throughout with broad theories and speculation. The writing is at once graceful and forceful. The book was very well received. Yet, his American colleagues wanted him to do more experiments and tried to bring him back to Woods Hole to do them. At the same time, his European friends were much more tolerant of his imaginative, but often not fully supported theories.

In recent years, as more has been written about holistic interpretations, Just has received more attention. Also he has been recognized as a pioneer in the new field, eco–devo, in which the emphasis is on the organism as a whole, studied as far as possible in its natural state (Byrnes and Eckberg 2006).

In reading Just's writing I was increasingly impressed by the fact that, despite clever ideas and meticulous work, workers in the field of development did not seem to be getting much closer to understanding basic mechanisms. I remember Jim Watson's once saying that until recently he had advised students to stay away from development; the tools were not ready. Now that the tools are here, the subject is taking off in a stampede. Just was too early.

ENVOI

How I wish Ernest Just had been born a century later. He would now be 25 years old, perhaps with a new Ph.D. He would have a totally different life. Racial inequities still have not disappeared, alas, but things are much better than in his time. A person with his talent, ambition, and work habits would surely find a place in a research environment.

When Just did his work, the most basic mechanisms of development could not be fruitfully attacked for lack of suitable techniques. Were he starting a career now, very likely he would be deeply involved in evo–devo, for evolution was always of great interest to him. And he would be taking advantage of all the powerful tools that the field of molecular genetics has made available. Alternatively, with his philosophical bent he might prefer systems biology, but he would have to learn some math. With his intelligence, hard work, and research drive he would surely thrive. And he would also experience that modern frustration—writing grant applications.

For a complete list of Just's publications, see Manning (1983). His scientific publications are listed in Just (1939b). For more details of his scientific accomplishments, see Byrnes and Eckberg (2006).

Acknowledgments

My greatest debt is to Kenneth Manning, whose biography of Just is thorough, scholarly, and sympathetic. It is based on an enormous amount of work—countless interviews and exhaustive library research.

Nature has neither core nor shell; she is everything at the same time. This quotation, from Goethe, was used on the title page of Just's definitive book (Just 1939b). It epitomizes his holistic view of the cell.

I am using the vocabulary of the time.

One enthusiastic Just supporter was Libbie Hyman, a student at the University of Chicago. She later wrote A Laboratory Manual for Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy, memorized dutifully if not enthusiastically by virtually every zoology student of my vintage. It was a best seller and she enjoyed pointing out that the royalties permitted her the leisure to work on her beloved invertebrates.

Later Loeb moved into more chemical subjects and became a founding father of protein chemistry, greatly respected for his innovation and his research standards (Loeb 1922; Cohen 1985). He was Sinclair Lewis's model for the character Gottlieb in Arrowsmith.

It is easy to see in this article why Just was regarded in some circles as hypercritical and arrogant. He did not hesitate to criticize Morgan, Jennings, Conklin, Demerec, and even his close friend Lillie, sometimes with sarcasm. Here is an example: “In passing, I may point out that Plough and Ives's statement of their method can not be called lucid” (Just 1936, p. 307).

References

- Byrnes, W. M., and W. R. Eckberg, 2006. Ernest Everett Just (1883–1941)—an early ecological developmental biologist. Dev. Biol. 296 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. S., 1985. Some struggles of Jacques Loeb, Albert Mathews, and Ernest Just at the Marine Biological Laboratory. Biol. Bull. 168(Suppl.): 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Crow, J. F., 1995. Quarreling geneticists and a diplomat. Genetics 140 421–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just, E. E., 1912. The relation of the first cleavage plan to the entrance point of the sperm. Biol. Bull. 22 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Just, E. E., 1919. The fertilization reaction in Echinarachnius parma. I. Cortical response of the egg to insemination. Biol. Bull. 36 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Just, E. E., 1922. Initiation of development in the egg of Arbacia. 1. Effect of hypertonic sea-water in producing membane separation, cleavage, and top-swimming plutei. Biol. Bull. 43 384–400. [Google Scholar]

- Just, E. E., 1932. On the origin of mutations. Am. Nat. 66 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Just, E. E., 1936. A single theory for the physiology of development and genetics. Am. Nat. 70 267–312. [Google Scholar]

- Just, E. E., 1939. a Basic Methods for Experiments on Eggs of Marine Animals. Blakiston's Sons, Philadelphia.

- Just, E. E., 1939. b The Biology of the Cell Surface. Blakiston's Sons, Philadelphia.

- Just, E. E., 1940. Unsolved problems in general biology. Physiol. Zool. 13 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lillie, F. R., 1942. Ernest Everett Just: August 14, 1883, to October 27, 1941. Science 95 10–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie, F. R., and E. E. Just, 1913. Breeding habits of the heteronereis form of Nereis limbata at Woods Hole. Mass. Biol. Bull. 24 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb, J., 1922. The explanation of the colloidal behavior of proteins. Science 56 731–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning, K. R., 1983. Black Apollo of Science. The Life of Ernest Everett Just. Oxford University Press, New York/Oxford.

- Wilson, E. B., 1925. The Cell in Development and Heredity, Ed. 3. Macmillan, New York.