8888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

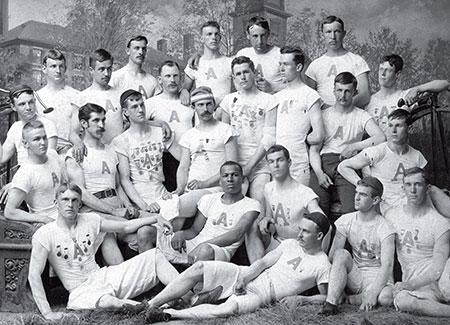

The Amherst track team in 1890, with Jackson in the front row, second from left.

By Evan J. Albright |

In 1892, when northern colleges were almost exclusively white, Amherst stood out for graduating three African-American seniors. Besides William Henry Lewis, the others were George Washington Forbes and William Tecumseh Sherman Jackson. One became an early leader in civil rights; the other a teacher.

George Washington Forbes, Class of 1892, was born in Shannon, Miss., in 1864. He moved to Boston after his Amherst graduation and helped launch a newspaper, the Boston Courant. In Boston, he joined William Henry Lewis and others in attempting to lead a revolt against the dominant force in African-American politics, Booker T. Washington. The Boston group believed that Washington was too willing to exchange civil rights, such as voting rights, for the economic opportunity to own property and businesses.

By 1903, however, Washington and Lewis, at the urging of President Theodore Roosevelt, reached a rapprochement. Forbes, along with William Monroe Trotter, had started a newspaper for African-Americans, The Boston Guardian, that frequently ran articles and editorials criticizing Lewis and Washington. The internecine conflict between the pro- and anti-Washington forces came to a head in July 1903, when Trotter and his supporters disrupted a speech by Washington in a Boston church. W. E. B. Du Bois would credit “The Boston Riot,” as it came to be known, with launching the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and by 1916 the NAACP’s more militant approach to civil rights replaced the accommodationist approach of Washington.

The Boston Riot was also a watershed for Forbes. Five years earlier he hyperbolically demanded that someone should “burn down Tuskegee,” Booker T. Washington’s school in Alabama; after the Boston Riot, Forbes found he no longer had the stomach for combative politics. He transferred his shares of The Boston Guardian to his classmate Lewis, eschewing politics for a quieter life as assistant librarian at the West Boston branch of the Boston Public Library.

William Tecumseh Sherman Jackson, Class of 1892, owed his college education to U.S. Senator George Frisbie Hoar of Massachusetts, who paid Jackson’s tuition and expenses. Jackson never forgot that kindness. He devoted his life to helping others obtain the same opportunities.

After leaving Amherst, Jackson moved to Washington, D.C., where he took up teaching at the M Street High School, later renamed Dunbar High School. He married May Howard, who would become one of the most famous African-American sculptors during the period known as the Harlem Renaissance. She made busts of several notable leaders of the time, including W. E. B. Du Bois and Paul Laurence Dunbar—and Lewis.

At Dunbar, Jackson taught mathematics and coached sports for 38 years. He served as the school’s principal from 1906 to 1909. He shepherded many of his students to Amherst, which graduated more Dunbar students than any other college outside of the nation’s capital.

It was Jackson who convinced Charles Hamilton Houston, Class of 1915, to attend Amherst. Houston became a prominent lawyer and the architect of

the legal challenge that resulted in Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court decision that in 1954 ended segregation in U.S. schools.

Jackson retired from Dunbar in 1931; his wife died a few months later. In 1942, Amherst honored him for his work as an educator. He died the following year.

8888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

When Lewis was appointed as an Assistant Attorney General in 1910, it was reported to be "the highest office in an executive branch of the government ever held by a member of that race."

[1] Before being appointed as an AAG, Lewis served for 12 years as a football coach at

Harvard University. During that period, he wrote one of the first books on football tactics and was considered a nationally known expert on the game.

Early years[edit]

Lewis was born in

Berkley, Virginia in 1868, the son of former slaves of European and African ancestry.

[2][3] His father moved the family to

Portsmouth and became a respected minister.

[3] At age 15, Lewis enrolled in the state's all-black college, the Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute (now

Virginia State University).

[4]

Football player and coach[edit]

Amherst College[edit]

With the assistance of Virginia Normal's president,

John Mercer Langston,

[4] Lewis transferred to

Amherst College, where he worked as a waiter to earn his college expenses.

[3] He also played football for Amherst for three seasons.

[2] In December 1890, the Amherst team voted "almost unanimously" to elect Lewis as the team captain for his senior year, 1891.

[5] He was also the class orator and the winner of prizes for oratory and debating.

[2]

All-American center at Harvard[edit]

Lewis cropped from 1892 Harvard football team photograph

After graduating from Amherst, Lewis enrolled at

Harvard Law School. He played two years for the Harvard football team at the

center position. An article published by the

College Football Hall of Fame noted that, while Lewis "was relatively light for the position (175 pounds) he played with intelligence, quickness and maturity."

[7] He was named as the center on the

College Football All-America Team in both years at Harvard. He was the first African American to be honored as an

All-American,.

[4][8][9]On one occasion when Lewis and the Harvard team entered a dining hall, the

Princeton University football team (which had many Southerners) rose as a group and exited in objection to the Negro player.

[10] In November 1893, Harvard's team captain was unable to play in the last game of the season due to an injury. The game was Lewis' last college football game, and the team voted him as the acting captain for the game, making him Harvard's first African-American team captain.

[4][11]

In announcing the All-America selections for

Harper's Weekly,

Caspar Whitney wrote that "Lewis has proved himself to be not only the best centre in football this year, but the best all-round centre that has ever put on a football jacket."

[12] In 1900

Walter Camp named Lewis to his All-Time All America Team, noting that Lewis's quickness had revolutionized center play, placing the emphasis on "mobility rather than fixed stability."

[12]

Following law school, Lewis was hired as a football coach at Harvard, where he served from 1895 to 1906.

[4] During his coaching tenure, the team had a combined record of 114–15–5.

[4] The Boston Journal wrote that Lewis was owed "much of the credit for the great defensive strength Harvard elevens have always shown."

[2]

Author and renowned expert on football[edit]

Lewis developed a reputation as one of the most knowledgeable experts on the game. In 1896, Lewis wrote one of the first books on American football,

A Primer of College Football, published by Harper & Brothers, and serialized by

Harper's Weekly.

[4][14] Upon the book's release, one reviewer noted:

A new feature, hitherto inadequately treated by previous authors, is the exhaustive treatment of fundamentals or the rudiments of the game, such as passing, catching, dropping upon the ball, kicking, blocking, making holes, breaking through and tackling. There is also a treatise on 'avoiding injuries' ... There are scientific expositions of team play, offensive and defensive, and a supplementary chapter on training which will be useful.

[15]

In a 1904 article,

The Philadelphia Inquirer placed Lewis on par with the legendary

Walter Camp in his knowledge of the game, writing, "The one man whom Harvard has to match Mr. Camp in football experience and general knowledge is William H. Lewis the famous Harvard centre of the early nineties and the man who is the recognized authority on defense in football the country over."

[16]

In 1905, critics of football sought to ban it from college campuses, or to alter its rules to control its violent nature. Lewis published an editorial in which he wrote, "There is nothing the matter with football. ... The game itself is one of the finest sports ever devised for the pastime of youth, and the pleasure of the public." While opposing unnecessary roughness, Lewis argued against proposed changes, noting that he did not want to watch "a game of ping-pong or marbles upon the football field."

[17]Lewis asserted that football should remain "a strenuous competition, a scientific game played according to the rules of the game with vigor and force, sincerity and earnestness."

[17]

Lewis later recalled, "There is no game like football. ... If it hadn't been for football there is no telling what I would be today. ... It gives you a general hardening and training which stands a man in good use in later life."

[18]

Politician and lawyer[edit]

President

Theodore Roosevelt, a friend of Lewis and a Harvard football fan, appointed Lewis as an Asst. U.S. Attorney in 1903.

Lewis entered politics by successfully running for election to the

Cambridge Common Council where he served from 1899-1902.

[19] He also was elected to the Massachusetts Legislature in 1901 for a single term, the last African American elected to that body for decades.

[19]

As a result of his Harvard football career, Lewis became a friend of President

Theodore Roosevelt, a Harvard alumnus, and was a guest of Roosevelt's at his estate at Oyster Bay, New York in 1900.

[20] In 1903 the United States Attorney for Boston

Henry P. Moulton, at the direction of Roosevelt, appointed Lewis as an Assistant United States Attorney in Boston; he was the first African American to be an Assistant US Attorney.

[21] His appointment was reported in newspapers across the country.

[22][23][24] Some wrote that the appointment was an effort by Roosevelt to show that "his championing of the negro is not political and is not limited to the southern states."

[25] The New York Times downplayed Lewis' race, noting, "Lewis is said to be so light in color that only his intimate friends know him to be a negro."

[26]

Some wrote that Roosevelt appointed Lewis in order to keep him in Boston, where he could continue coaching the Harvard football team. The author noted that Lewis "owes his appointment to the fact that he is an uncommonly good football coach and that President Roosevelt is a Harvard man."

[27] Cornell has made several attempts to hire Lewis as its football coach. According to the story, Harvard men were "unwilling to lose Lewis's services in the football season, and they undertook to make his residence here so profitable that he would remain."

[27]

First African-American Assistant Attorney General[edit]

In October 1910, President

William Howard Taft announced he would appoint Lewis as an

United States Assistant Attorney General, sparking a national debate. A North Carolina newspaper wrote that the "Lucky Colored Man" would hold the "Highest Public Office Ever Held by One of His Race."

[1][28] The appointment was reported to be "the highest office in an executive branch of the government ever held by a member of that race."

[29][30][31] The Boston Journal wrote that Lewis had received "the highest honor of the kind ever paid to a negro," such that he then ranked in "a position of credit and influence second only to that occupied by

Booker T. Washington.”

[32]

The Washington Evening Star concluded that the appointment of Lewis to "a higher governmental position than any heretofore given to a colored man" would result in a confirmation battle with southern Democrats.

[33] An Illinois paper mistakenly reported in December 1910 that opposition to Lewis was so strong that Taft had decided not to place his appointment before the Senate.

[34] But, Taft did not withdraw the nomination, and a Georgia newspaper predicted a "Hard Fight Is Coming" on the nomination:

Many southern members are firmly resolved that Lewis shall never be elevated to the high post of one of the five assistant attorneys general. The position carries with it a handsome salary, high social position and an entrée to White House functions. Whether or not Lewis would ever avail himself of these privileges, a number of southern Democrats feel that they do not want to be a party to elevating him to an eminence where such recognition would be his as a matter of official right.

[35]

After a two-month fight against him waged by the Southern Democratic block (Southern states had disfranchised most blacks at the turn of the century and white Democrats dominated southern politics), the Senate confirmed Lewis as an Assistant Attorney General in June 1911.

[36] After being sworn into office, Lewis went to the White House, where he personally thanked President Taft for the high honor.

[37] Lewis' initial assignment was to defend the federal government against all Indian land claims.

[37] Lewis was a frequent caller at the White House and regularly attended White House functions during the Taft administration.

[38]

Challenge from southern ABA members[edit]

Attorney General

George W. Wickersham sent a "spirited letter" to all 4,700 members of the ABA after the ouster of Lewis

In 1911, Lewis was among the first African Americans to be admitted to the

American Bar Association (ABA).

[8][9] In September 1911, Lewis faced a campaign for his ouster from the ABA. Though there was no racial restriction in the organization's charter, some members threatened to resign if Lewis stayed. When Lewis' name had been submitted with others by the Massachusetts Bar Association, his race had not been disclosed. The Southern white delegates said they did not know he was a

negro until he entered the convention hall.

[39] Lewis refused to resign.

[40]

When the ABA's executive committee voted to oust Lewis in early 1912, U.S. Attorney General

George W. Wickersham sent a "spirited letter" to each of the 4,700 members of the ABA condemning the decision.

[41][42] While northern newspapers congratulated Lewis and Wickersham for their stance,

[43] a North Carolina newspaper criticized Lewis for his lack of "good manners" in refusing to resign:

The insistence of William H. Lewis of Boston, now an Assistant Attorney General, that he retain his membership in the American Bar Association notwithstanding objections is due condemnation upon other grounds than those of race. He would probably not have been elected if it had been known by the majority of delegate who he was. Having thus slipped into an organization, he should offer his resignation pending a real decision of the matter. This is simply what any one elected to any manner of organization through any sort of ignorance or misapprehension is required by good manners to do.

[44]

Lewis became an advocate for African Americans in the legal profession. During the fight over his removal from the ABA, Lewis published an article saying that many white men "know intimately only the depraved, ignorant, vicious negros – those who helped to keep the dockets filled."

[45] He called for blacks to train and form "an army of negro lawyers of strong hearts, cool heads, and sane judgment", to help the large number of African Americans who were "exploited, swindled and misused".

[45]

Private law practice[edit]

Lewis's tenure as Assistant Attorney General ended with Taft's presidency in 1913, as these are political appointee positions tied to particular administrations. Taft recommended Lewis for appointment as a Massachusetts Superior Court judge, but the state's governor,

Eugene Foss, declined to make the appointment.

[46] Lewis returned to Massachusetts and entered the private practice of law. He developed a reputation as an outstanding trial lawyer and appeared before the United States Supreme Court on more than a dozen occasions.

[19] He remained active in Republican politics while practicing law. Among his cases, he represented persons accused of bootlegging and corruption, in addition to those challenging racial discrimination.

[47]

Civil rights leader and speaker[edit]

Lewis was a speaker at Boston's memorial for famed abolitionist

Julia Ward Howe.

Throughout his career, Lewis was outspoken on issues of race and discrimination. After a white barber in Cambridge refused to shave Lewis, he filed a suit seeking $5,000 in damages and successfully lobbied for the passage of a Massachusetts law prohibiting racial discrimination in places of public accommodation.

[46][47][48][49]

In 1902, Lewis delivered an address on race relations to a gathering of Amherst College alumni. Lewis called race the "transcendent problem" facing the country, referring to the recent

Spanish–American War, the

disfranchisement of blacks in the South by new state constitutions, and the imposition of

Jim Crow, which deprived blacks of civil rights, in his remarks:

Yesterday the United States waged a war for humanity when tyranny and oppression had grown intolerable. … Only a few hundreds of miles south of us are 10,000,000 people who are deprived of their rights, who are practically in a state of serfdom. Thousands of them have been

lynched and shot for attempting to exercise the God given rights of every human being. The great Democratic party rolls on its honied tongue the sweet morsels of 'consent of the governed' and 'equality of man.' The Republican Party, progressive, patriotic, absorbed with expansion, is too busy to disturb the harmony of the spheres. They stand opposite making grimaces at each other; one says 'Filipino;' the other hasn't the courage to say 'Nigger.' It is a beautiful game of football with the negro as the football.

[50]

Love your native Southland. Nine tenths of our people were born here. All our past is here. All our future is here. Here most of us will live and here pass to the great majority and be gathered to the ashes of our fathers. The most glorious history of our race is here in the Southland, the most glorious history of the negro race anywhere in the world is here. If we have suffered here, we have also achieved greatly here. Rejoice in everything Southern.”

[51]

While serving as Assistant Attorney General, Lewis learned that a young African-American graduate of Harvard had been refused employment at a prominent Boston trust company on account of race. In a speech to Boston business leaders, Lewis said: "In Boston the outlook for the negro is far worse than it has been since the Civil War. I think the blood of three signers of the Declaration of Independence and of the Abolitionists has run out."

[52] He noted that, if he owned the majority of stock in a certain trust company, he would force the company to hire "the blackest man in Boston."

[52] Lewis' speech reportedly drew "volumes of cheers" from the businessmen and "also from the colored waiters who cheered frequently."

[52]

Lewis was one of three persons invited to deliver an address at Boston's Symphony Hall memorial to

abolitionist Julia Ward Howe following her death in 1910.

[53]

In 1919, Lewis was one of the signatories to a call published in the

New York Herald for a National Conference on

Lynching, intended to take concerted action against the widespread practice of lynching and lawlessness in primarily Southern states.

[54] Lynching had reached what is now seen as a peak in the South around the turn of the century, the period when those states imposed white supremacy.

[55] In the summer of 1919, after Lewis' speech, the economic and social tensions of the postwar years erupted in numerous white racial attacks against blacks in northern and midwestern cities where blacks had

migrated by the thousands and were competing with recent European immigrants; it was called

Red Summer.

8888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

8888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888